Gut hormone can curb sugar cravings

The hormone may prove to be an effective weapon against obesity, and the discovery was made by a team of researchers from the University of Copenhagen.

People love sugar – it delivers comfort and reward, and it’s delicious!

But why do most of us feel we’ve had enough after a couple of pieces of cake or a large portion of ice cream? And why don’t we simply keep on eating sugar once we’ve started? What stops us?

This is the question eight researchers from the University of Copenhagen’s (UCPH) Department of Biology may have found part of the answer to.

Small-scale surgery on the insides of a fruit fly

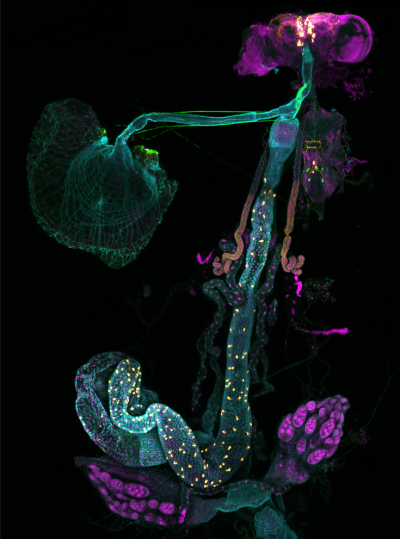

Researchers at the Department of Biology at UCPH used a special postmortem technique to remove the brain, entire central nervous system, entire gut and reproductive organs (i.e. the ovaries) from a female fruit fly, a mere three to four millimetres in length.

Everything was removed as a single, connected organ system – something which, as far as is known, has never been done before.

‘This is truly small-scale surgery, conducted with tiny, razor-sharp tweezers,’ Professor Kim Rewitz explains.

The organ system was then stained with fluorescent agents, enabling the researchers to see the various organs and relevant cell types on a microscopic image. The image is created using a scan taken with a so-called confocal microscope.

The yellow dots on the image represent the NPF gut hormone. This hormone is the fruit fly’s “sugar brake”, and NPF is extremely similar to the PYY gut hormone found in humans and other mammals.

In experiments with fruit flies, they have succeeded in revealing what a certain gut hormone – a hormone that also helps regulate appetite in humans and other mammals – actually does. The answer was recently published in a research article in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Metabolism.

In simple terms, the article demonstrates that, in fruit flies, this gut hormone acts as a kind of “sugar brake”, a biological mechanism that prevents the fly from uncontrollably filling itself with sugar and leaving no room for other nutrients. And Professor Kim Rewitz, who headed the project, explains that it is fairly likely that the version of this hormone found in mammals – PYY– acts in the same way.

‘We were aware of the existence of PYY – which belongs to a large group of so-called appetite-regulating hormones formed in the gut of humans and other mammals – but weren’t sure of its entire function. So, this was the function we studied in the fruit fly experiments. And we could do this because fruit flies have a gut hormone very similar to PYY.’

The experiments showed that when fruit flies eat sugar, specific cells in their guts produce the hormone equivalent to human and mammalian PYY. And Professor Rewitz says that there was quite a surprise in store for the UCPH researchers when they recorded the results.

‘We could see that the fruit fly version of the PYY hormone lowered the flies’ appetite for sugar and increased their appetite for food rich in protein. So, it acted as a kind of sugar brake and made them hungry for more nutritional food.’

But would this also apply to humans when eating sugar?

‘It’s quite probable that the PYY hormone also acts as a sugar brake in mammals – so, in humans too. We’re not sure of this yet but it ought to be investigated. Because, if it is the case, it could potentially pave the way for numerous interesting opportunities for therapies based on PYY to combat obesity by suppressing appetite for sugar and increasing craving for protein,’ suggests Rewitz, whose research has received funding from the Lundbeck Foundation in the form of an Ascending Investigators grant.

Highly useful flies

A single fruit fly is fairly inconspicuous, whether in a test tube in a lab or hovering over a fruit bowl on the kitchen counter. It is a mere three to four millimetres long and may not seem to have a lot in common with either a mammal or a human being.

But make no mistake. The fruit fly, or Drosophila by its Latin name, has a long list of well-documented, basic biological characteristics in common with mammals. As Professor Rewitz explains, this fly is therefore extremely suitable and much used as a model organism in biological experiments.

‘To conduct our study of this special gut hormone, we used genetic engineering to switch off the genes that control production of the fruit fly version of PYY. We then gave the flies free access to sugar, and their appetite was unquenchable because they no longer had a brake. After some time, we injected them with the hormone we had temporarily prevented the cells in their gut from producing, and shortly afterwards they stopped eating the sugar and turned to the protein we also offered. That was how we discovered the sugar brake.’

You need a steady hand to give a fruit fly a hormone injection, says Professor Rewitz:

‘The needles we use are made of glass, and their tips are only a few hundredths of a millimetre thick. We place the fruit fly under a microscope and manoeuvre the needle by hand. It’s not that difficult with a bit of practice, and once you’ve found the right place on the fly, all you need to do is jab. Directly into the blood.’