Mini-Brains to shed light on nervous disorders

Martin Røssel Larsen’s project is receiving a grant of DKK 35 million from The Lundbeck Foundation

When a foetus’s brain does not develop normally, it may mark the beginning of a brain disorder that will come to light later in life.

However, it can be difficult to identify the details underlying a correlation between early-stage malformation and later outbreak of disease because, for a number of practical and ethical reasons, this cannot be studied directly in humans.

In this situation, it can be necessary to apply other, more indirect, study methods – and this is the reasoning behind the project for which Martin Røssel Larsen has received a Collaborative Projects grant worth DKK 35 million.

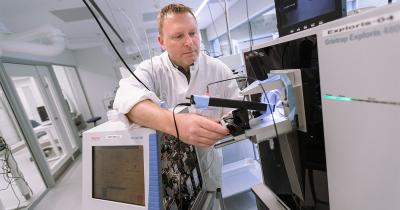

Martin Røssel Larsen is a professor at the University of Southern Denmark’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and he works with so-called brain organoids, more popularly referred to as mini-brains.

If you conduct a Google search for “Martin Røssel Larsen, minihjerner”, one of the first hits will be a YouTube video in which the professor explains in Danish what mini-brains are. And they are by no means a brain in the traditional sense.

A mini-brain is a biological system – a large lump of living human brain cells, only a few millimetres in size, stored in nutrient fluid in a Petri dish in a special growth chamber in the lab.

The mini-brain has around one million cells, and therefore, also in this respect, is a lot smaller than a real human brain, which has many billions of cells.

If you cultivate a mini-brain in the laboratory from human stem cells, it can be used to simulate early stages of the development of the brain of a human foetus.

By cultivating mini-brains based on stem cells taken from schizophrenia patients, Martin Røssel Larsen and his colleagues hope to create a foundation for a range of studies of schizophrenia.

Among other things, they will be able to study changes in signalling patterns during the early stages of brain development, and then compare these findings with similar observations of mini-brains grown from stem cells taken from individuals who do not suffer from schizophrenia.

The hope is that this will provide new knowledge about the biological mechanisms of schizophrenia – resulting in ideas for new types of treatment for this mental illness.

Martin Røssel Larsen’s co-applicants and partners are:

Madeline Lancaster, head of a research group at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK; and Associate Professor Kristine Freude and Professor Poul Hyttel, both from the Department of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, University of Copenhagen.